Welcome back to our ecological restoration series! Last time, we learned about Haddington Woods. Up next, we’re talking about FDR Park.

Why was ecological restoration necessary in FDR Park?

Ecological restoration involves rebuilding ecosystems that have been disrupted, often due to human activity, biodiversity loss, and climate change. FDR Park has been hit particularly hard by these challenges, with frequent flooding, illegal dumping, and more.

The southwest corner of FDR Park is the historic low point of the park and it has a long history of disturbance. From a railway bisection to highway construction, to the demolition of a water pollution plant and decades of disorganized and illegal short dumping, about 15 feet of soil and debris was piled onto that low point.

At the same time, the park’s tide gate, a device used to control tidal river water, was failing and couldn’t accommodate the hotter, wetter climate. The soil and debris that had accumulated in recent decades were clogging the natural flow and preventing drainage of water throughout the park.

The former construction dumpsite has been consistently disturbed and degraded by human activity and the effects of climate change, while the edge of the site was struggling to establish a forest. Unfortunately, the forest was not healthy and not showing signs of establishing a trajectory to a higher quality, higher functioning ecological system. Phragmites, an invasive species, had taken over and displaced native plants and animals.

As part of the FDR Park Plan and a key component of the Ecological Core of the reimagined 348-acre park, the Philadelphia International Airport, in partnership with Fairmount Park Conservancy and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, embarked on a project in 2022 to transform the previously inaccessible site into a 33-acre urban tidal wetland system.

What are wetlands?

Wetlands, areas regularly covered or saturated by water, act as “green sponges” that absorb water after rain and tidal events. They play a crucial role in slowing down floodwaters, capturing and storing water, recharging groundwater, and enhancing nutrient uptake by vegetation. Moreover, wetlands act as natural filters, improving water quality by removing pollutants from surface water flow. Surface water is defined as any body of water above ground, including streams and rivers.

Despite covering only 1% of Earth’s surface, wetlands play a vital role in ecological health, capturing and storing approximately 20% of ecosystem organic carbon. They do a lot of heavy lifting by storing carbon that would otherwise get released into the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. A study conducted by Dutch, American, and German scientists found that wetlands capture about five times more CO2 than forests and up to 500 times more than oceans.

What has been done so far?

As the FDR Park wetland project got underway, excavation was a significant aspect of the project, removing decades of accumulated soil, debris, and materials. The process involved thorough soil testing during which contaminated soil was removed and suitable soils were retained on-site, creating a temporary soil hill that will be planted with natural grasses.

A.P. Construction, a general construction firm, supported the wetland’s creation by repairing and retrofitting the drains in the park that connect the wetland to the Naval Reserve Basin. Retrofitting is the installation or improvement of stormwater management practices to provide a water quality function and mitigate flooding. Water flows into FDR Park from the tide and creeks, making this a large effort.

Two new tide gates were established to replace the malfunctioning tide gate in the Naval Reserve Basin, along with a trash rack to prevent debris from clogging the piping system. The new tide gates are more accessible for park staff to maintain, and prevent river water from backing up into the park at high tide. The tide gates were reopened last fall, reconnecting the park with the Delaware River.

The team of ecological engineers from Biohabitats, a firm that specializes in creating nature-based solutions to challenges like those found at FDR Park, then monitored the water levels, where they were coming from, and whether the water was going in the right direction. After that observation, they implemented an adaptive grading plan and made minor adjustments in the lay of the land to raise certain areas and lower others to ensure proper distribution of water across the wetland.

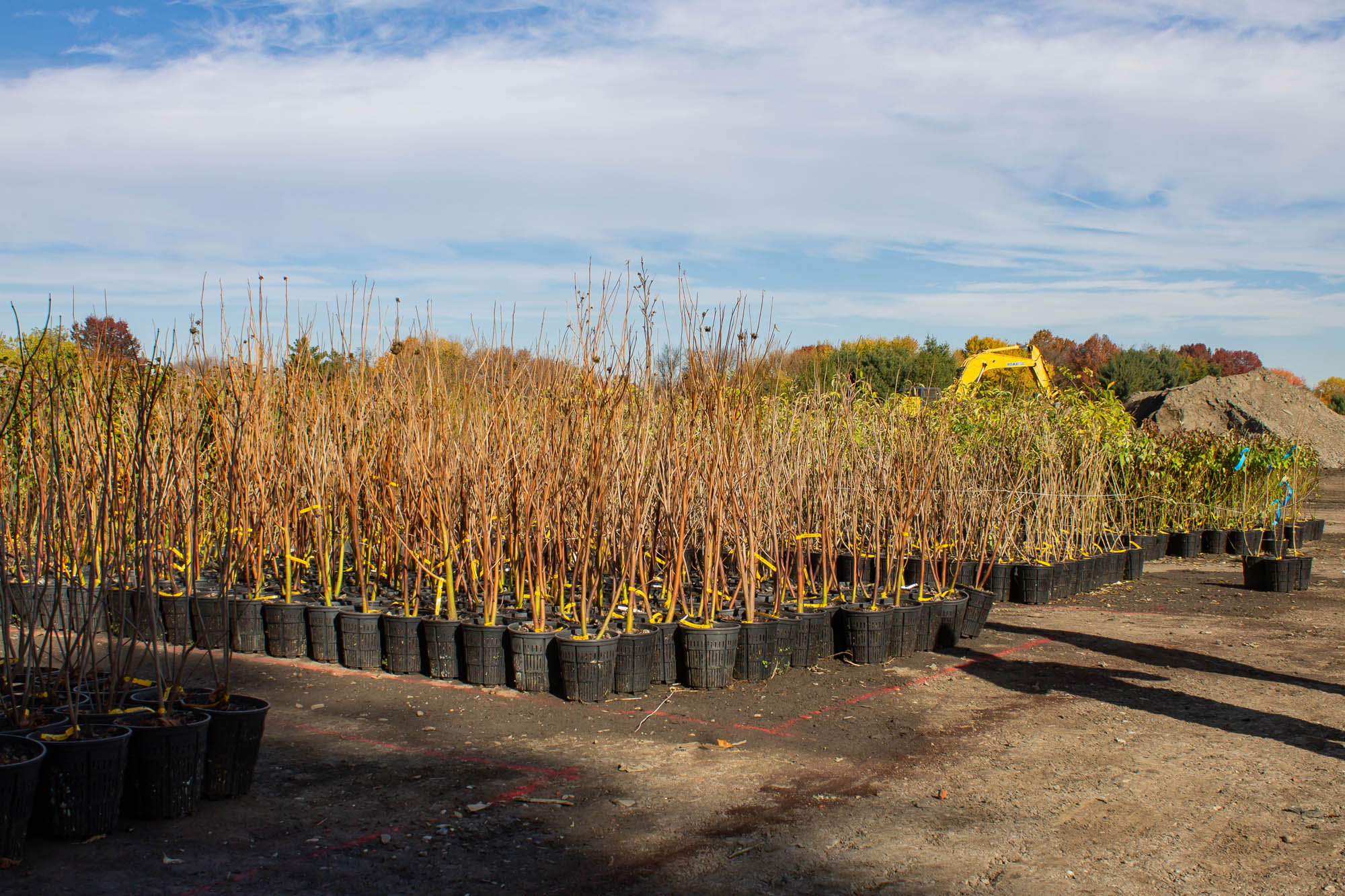

Image captured by the Philadelphia International Airport

In late 2023, approximately 7,000 trees and 1,700 bushes and woody shrubs were planted in the wetland. Since the park is situated between the Schuylkill River and the Delaware River, species native to coastal zones in Pennsylvania were selected, including willow oaks, sweet bay magnolias, river birches, and more.

In contrast to the poor quality forest that was cleared, the planted trees and shrubs will form a diverse native plant community. These native plants host native pollinators and other insects that feed migrating birds and provides fruits and seeds throughout the year to feed wildlife. The mix of fast-growing trees, like willows and sycamores, and slow-growing trees, like oaks, will develop into a more resilient and healthy forest through a process called succession.

What’s next?

More than 30,000 plugs, also known as young plants, will be installed this spring and emerge as vegetation that will grow out of the water. This vegetation provides nesting habitats and food for songbirds, and cover from predators for juvenile fish and amphibians. It also serves as a carbon sink and natural filter by trapping sediment, nutrients, and other debris. Geese like to eat young plants, so these plants will be monitored as well to allow them to grow and prevail.

To maintain the site, the Biohabitats team will keep an eye on invasive species, such as phragmites. While considerable effort went into properly removing the phragmites that were previously taking over the site, they still could return and take over the new wetland without proactive monitoring. Deer, a native species that is invasive due to having no natural predators, will be managed with a deer fence while these new plantings are being established.

Ecologists working on the project are eager to see the wildlife benefit from the work underway. Species such as turtles, frogs, birds, and more were surviving in the old ecosystem, but this wetland project will expand habitats and create more space for wildlife to thrive, increasing biodiversity while combating flooding exacerbated by climate change.

Mike Trumbauer, a senior ecologist at Biohabitats, said this project is gratifying, especially during his commute over the Girard Point Bridge, where he can see the wetland along Philadelphia’s skyline.

“Just knowing that it was a dump site, and now every time I go, I see something different. We’ve seen eagles do aerial acrobatics,” said Mike, “There was ecology there from the start. I’m just happy we’re adding to it. That’s always rewarding.”

This large-scale, transformative tidal wetland project will add a new waterbody to the park for the first time in a century. Anticipated to be complete in 2025, the project will undergo extensive post-construction monitoring to ensure its long-term success.

This blog post is part of a series. Read more ecological restoration blog posts here!